Kelp forests sequester carbon in fundamentally different ways from soil-based blue carbon ecosystems. Rather than storing carbon beneath the forest, kelp exports organic carbon into the ocean as drifting particles and dissolved compounds. This article explains how these pathways work, how long kelp-derived carbon can remain stored, and why tracking permanence requires oceanographic models rather than sediment measurements alone.

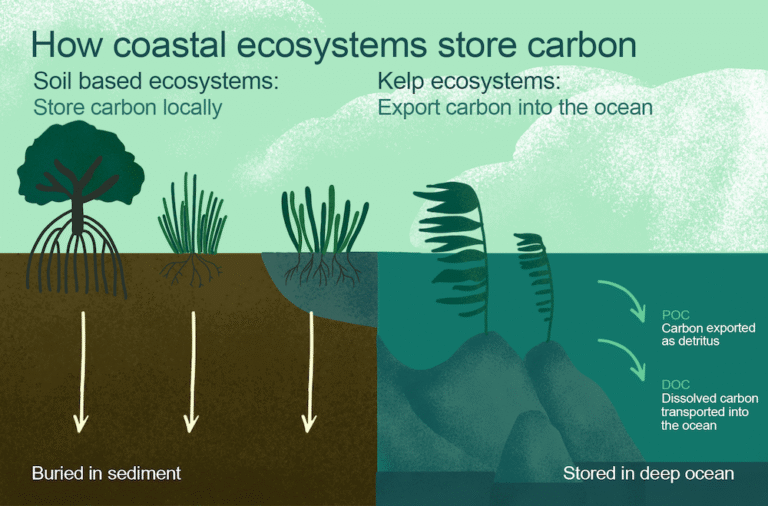

Kelp forests play an important role in the global carbon cycle, but they work very differently from other blue carbon ecosystems. Mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes use root systems to trap and store carbon directly beneath them in soils and sediments. Kelp, by contrast, has no true roots. Instead, it anchors to rocky reefs with a holdfast that secures the plant but does not store carbon. Kelp individuals also live for only a few years, much shorter than trees, so most of the carbon they capture is stored only temporarily before being shed. Once released, this carbon leaves the forest as drifting fragments or dissolved compounds, which may travel far from where it was produced. Because this carbon is dispersed rather than stored on site, it is much harder to track and verify. This is a key reason kelp has not yet been included in formal blue carbon frameworks (Hurd, 2022; Krause-Jensen & Duarte, 2016).

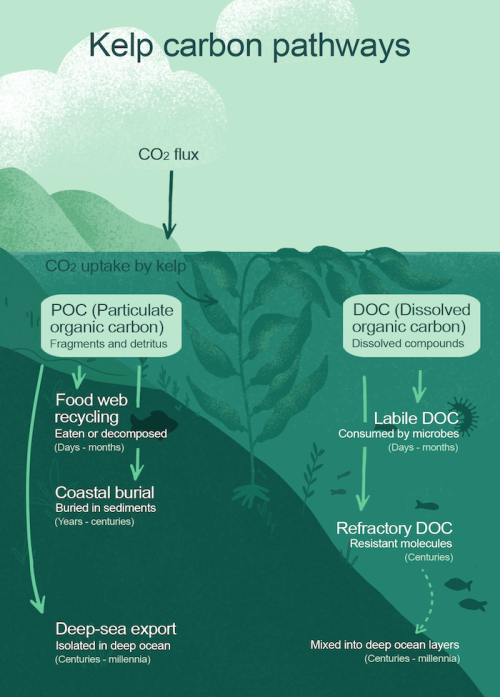

Kelp moves carbon into the ocean in two main forms: particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC). These behave very differently and are tracked using different approaches.

POC refers to both large and small pieces of kelp tissue, from visible fragments like blades and stipes to tiny particles that are still solid but not fully dissolved in seawater. These are often defined by their ability to be caught on filters rather than passing through as DOC. Some of this material is quickly eaten or decomposed in coastal waters, while other particles are carried by currents over long distances. Under the right conditions, POC can settle into sheltered nearshore sediments or reach deep-sea environments like fjords and submarine canyons (Krause-Jensen & Duarte, 2016; Macreadie et al., 2023). Scientists investigate this pathway by modelling ocean currents and by tracing kelp material found in seafloor sediments (Macreadie et al., 2023; Filbee-Dexter & Wernberg, 2020).

DOC, in contrast, is released while kelp is alive. These carbon compounds dissolve straight into seawater. Most are quickly consumed by microbes, but some are resistant to breakdown, known as refractory DOC (rDOC) (Li et al., 2022; Weigel & Pfister, 2020). Brown algae produce compounds like fucoidan, a sugar-like molecule that can remain in marine sediments for centuries (Buck-Wiese et al., 2023). Researchers measure DOC by sampling seawater around kelp forests, analysing its chemistry and how fast it decomposes.

How long kelp carbon remains stored depends on the route it takes once it leaves the forest.

DOC, especially rDOC, tends to last the longest. Once it mixes into the ocean’s dissolved carbon pool, it is largely out of reach of microbes and can stay there for centuries before slowly breaking down (Li et al., 2022; Buck-Wiese et al., 2023).

POC can also contribute to long-term storage if it sinks deep enough. When fragments are transported below about 1,000 metres, they are effectively isolated from the surface carbon cycle and can remain out of contact with the atmosphere for centuries to millennia (Krause-Jensen & Duarte, 2016).

A third pathway is burial in sediments. In undisturbed, low-oxygen seafloor environments, kelp detritus can be buried and preserved for long periods. But in more energetic coastlines, waves and currents can stir the seabed, re-suspending the material and allowing it to decompose more quickly (Macreadie et al., 2023).

These pathways differ sharply from soil-based blue carbon systems, where carbon is stored directly beneath the plants in stable soils. Because kelp relies on mobile pathways that depend on ocean transport, its permanence is harder to measure, but it can be studied with oceanographic models that estimate where exported material ends up (Pessarrodona et al., 2024).

Measuring long-term kelp carbon storage is challenging because kelp does not accumulate carbon directly beneath its canopy. Once exported, kelp mixes with other organic matter, making it hard to prove its origin. Conditions also vary greatly between regions; local currents, wave exposure, depth, and seafloor type all influence whether carbon settles or is recycled (Macreadie et al., 2023). Because most of these processes cannot be observed directly, researchers rely on ocean modelling to estimate how much kelp carbon reaches long-term storage sites (Pessarrodona et al., 2024).

To help close this gap, researchers are developing new tools. For example, environmental DNA (eDNA) can detect kelp’s genetic traces in sediments, showing where fragments end up, like finding a DNA trail at a crime scene. Scientists can also look for unique chemical “fingerprints” of kelp compounds in seawater and sediments, or compare natural isotopic “labels” in kelp with those found in buried material (Macreadie et al., 2023). These approaches are still emerging but are giving clearer evidence of where kelp carbon goes and how long it lasts.

How far kelp carbon travels and whether it becomes long-term storage depends on biological, physical, and environmental factors.

Carbon production and export differ by kelp species and site type. Fast-growing canopy formers like Macrocystis in upwelling regions produce more biomass than slower-growing species like Laminaria. Upwelling areas supply a steady flow of cold, nutrient-rich water, creating favourable conditions for rapid kelp growth. By contrast, species in more stable or nutrient-poor environments grow more slowly and export less carbon. Restoration or farm sites often have more uniform stands than wild forests, which also influences production and export rates (Krause-Jensen & Duarte, 2016; Pessarrodona et al., 2024).

Water quality parameters such as nutrient levels, light availability, and temperature also influence much growth and decomposition rates.

Local oceanography influences transportation and dispersal. As Broch et al. (2022) showed, most detritus from sheltered Norwegian kelp farms settled within 1 km, whereas at exposed sites it travelled tens of kilometres and settled at much greater depths. Similarly, Filbee-Dexter et al. (2022) reported that exported kelp in the North Atlantic often accumulates in nearby fjords, while in energetic Australian coasts much less material reaches the seafloor.

Material traits like tissue density, toughness, and buoyancy affect how long fragments survive in transport (Pessarrodona et al., 2024). Finally, tools such as eDNA and chemical fingerprints are increasingly used to confirm deposition zones (Macreadie et al., 2023).

On a per-area basis, reported rates vary widely depending on which pathway is considered and how it is measured. For example, sediment burial directly beneath long-term kelp farms has been measured at up to ~8 t CO₂ eq ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ (Duarte et al., 2025), while other studies suggest much lower values in more energetic sites. When scaled across the ~7–8 million ha of global kelp forests (Krause-Jensen & Duarte, 2016), even conservative estimates translate into several Mt CO₂ per year, with higher-end scenarios potentially exceeding 50 Mt CO₂ annually. For context, this range spans from the annual emissions of a small country like Luxembourg at the low end to mid-sized nations such as Switzerland or Denmark at the high end.

Kelp forests move carbon through the ocean in two main forms

Particulate organic carbon (POC), which breaks off as drifting fragments, and dissolved organic carbon (DOC), released while the kelp is alive.

Unlike soil-based blue carbon habitats that lock carbon beneath them, kelp carbon is exported away from where it’s produced, making it harder to track but possible to model using oceanographic tools.

Permanence depends on where the carbon ends up: rDOC can persist for centuries in the dissolved pool, POC can be locked away for centuries to millennia in deep waters, and some material becomes buried in low-oxygen coastal sediments.

Measuring these pathways is challenging because most kelp carbon mixes with other organic matter once dispersed. Researchers use models, oceanographic data, and emerging tools like eDNA, isotopes, and biomarkers to detect where kelp carbon goes.

Scientists are only beginning to understand how much carbon kelp can lock away and for how long. Current global estimates are rough, because kelp carbon doesn’t stay under the forest itself but is carried away into the ocean. This makes it harder to measure directly and explains why results vary so widely between regions. In some places, studies suggest kelp may store carbon at rates similar to seagrasses or salt marshes, while in others the contribution is very small (Filbee-Dexter et al., 2022; Pessarrodona et al., 2024).

What is clear is that kelp is part of a major natural carbon flow that scientists are only now beginning to map properly. New methods, such as ocean models that track drifting kelp and tools that detect kelp traces in seawater and sediments, are helping to reveal which species and locations are most important for long-term storage (Macreadie et al., 2023; Filbee-Dexter et al., 2024). As this research expands, we can expect much clearer numbers and a better sense of kelp’s role in the global carbon budget.

Hurd, C.L. (2022). Forensic carbon accounting: Assessing the role of seaweeds for carbon sequestration. Journal of Phycology, 58(4), 503–507.

Krause-Jensen, D. & Duarte, C.M. (2016). Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nature Geoscience, 9, 737–742.

Macreadie, P.I., et al. (2023). Seaweed carbon export is a substantial global flux to the deep ocean. Nature Geoscience, 17, 343–350.

Filbee-Dexter, K. & Wernberg, T. (2020). Substantial blue carbon in overlooked Australian kelp forests. Scientific Reports, 10, 12341.

Li, H., et al. (2022). Carbon sequestration in the form of refractory dissolved organic carbon in a seaweed (kelp) farming environment. Science of the Total Environment, 838, 156158.

Weigel, B. & Pfister, C.A. (2020). Dynamics of dissolved organic carbon in kelp forests. [Exact journal details not provided in the page].

Buck-Wiese, H., Wietz, M., Wemheuer, B., et al. (2023). Fucoid brown algae inject fucoidan carbon into the ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(1), e2210561119.

Pessarrodona, A., Howard, J., Pidgeon, E., Wernberg, T., & Filbee-Dexter, K. (2024). Carbon removal and climate change mitigation by seaweed farming: A state of knowledge review. Science of the Total Environment, 918, 170525.